http://www.stephanie-osborn.com

Last week best-selling author Christopher Nuttall discussed the historicity of the concepts of love, romance, sex, and marriage, presenting information important to the modern reader (or writer!) of historical fiction, with a special emphasis on the Regency period. But Chris writes science fiction and fantasy, and does so quite well, both self-published and through presses like Twilight Times Books and Elsewhen Press.

So let's pick up where we left off, and let Chris tell us how he wielded the element of romance in his own books.

~~~

Chris:

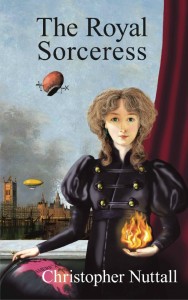

...And now I come to talk about one of my characters and her first true romance. [The Royal Sorceress]

Lady Gwen was born in a world where the

principles of ‘sorcery’ – actually, mental powers – were discovered prior to

the American Revolution. This caused a

flowering of technology, but it also caused major social problems, particularly

as magic helped the British Empire defeat the American rebels and crush the

American Revolution. By the time of the

first story, the British aristocracy is firmly in control, but unrest simmers under

the surface of Britain.

Lady Gwen was born in a world where the

principles of ‘sorcery’ – actually, mental powers – were discovered prior to

the American Revolution. This caused a

flowering of technology, but it also caused major social problems, particularly

as magic helped the British Empire defeat the American rebels and crush the

American Revolution. By the time of the

first story, the British aristocracy is firmly in control, but unrest simmers under

the surface of Britain.

Gwen developed magic – powerful magic –

fairly early in life. This became public

very quickly, making it impossible for Gwen’s parents to arrange a marriage for

her. (What man wants a wife who can kill

him with a thought?) In a world where

noblewomen were expected to be decorative, go to balls and marry someone their

parents chose, Gwen lived a fairly isolated life, seething with frustration at

not being able to do anything with herself.

By the time she was recruited for the Royal Sorcerers Corps (in the

absence of a suitable man) she wanted desperately to prove herself. But she could also be largely unaware of the

dangers of the world.

In her second book, The Great Game, Gwen was courted by a man who came into her life as

part of a murder investigation. Sir

Charles seemed, in every aspect, the perfect regency hero; brave, handsome,

noble and true. But how was he to court

her? Normally, any man interested in

courting a girl in the era would invite her to a dance, then declare his

intentions to her parents. And yet, Gwen

was as independent as any woman could hope to be – perhaps more so – in that

time and place. To approach her parents

would have been disastrous.

Sir Charles understood his prey (and he was

hunting her) very well. He approached

her openly, made himself useful, and invited her to ride with him. By showing no fear (because of her magic) or

contempt (because of her sex) he made a very good impression on someone who had

spent little time with men, socially.

Gwen reacted well, perhaps better than he had hoped, and they

kissed. But they went no further. By refraining from pushing her, Sir Charles

earned her respect. Perhaps he even

earned her love.

But his very approach should have been a

warning that he had something else in mind.

An honourable man would, perhaps, have approached her parents, even

though it would have annoyed Gwen. A

marriage in those days wasn't just a match between a boy and a girl; it was a

match between two families. If they had

married, Gwen’s family would have been tangled with Sir Charles’s family. The consequences of their relationship would

have spread further than just the two of them.

Gwen didn't realise, until it was almost

too late, just how badly he was playing her.

He wasn't interested in luring her into bed, but in manipulating the

outcome of the investigation and – if necessary – betraying her. In hindsight, the signs were all too

clear.

This shouldn't have been surprising. Georgian and Victorian noblewomen lived a

very sheltered life. They were coddled

and protected from the worst of the world outside their walls. Those women that might have served as

examples of the dangers were often driven into social obscurity or death. Indeed, medical textbooks of that period

often concealed details concerning sex and women’s bodies, even though many

details were blindingly obvious. (A

quick look in the mirror would have shown the curious woman that some of the

details were wrong.) But they were not

encouraged to develop any form of curiosity.

A wedding night could be a frightening introduction to the world of sex.

There were fewer restrictions on men. Men were expected to sow their oats in

brothels, which were populated by women of the lower classes (and thus not considered

completely human.) A woman who disliked

her husband had no easy way to leave him (to some extent, she was his property), while the husband could find solace in the arms of a mistress – or a

whore. Female adultery, on the other

hand, would face significant punishment.

A husband could even sue his

wife’s lover, on the grounds that his property had been damaged. It is surprising that there were any cases of

adultery at all.

Depicting a romance – or a cold and

calculating attempt at seduction – in such a society can be tricky. Will the author, depicting a world where

women are expected to be subordinate (at least in public) be accused of

sexism? Or will the author, showing an

underage marriage (by our standards), be accused of condoning paedophilia? Or will the author, showing a mixed-race

marriage in 1900, be accused of racism if he depicts the likely reaction of

most contemporaries to such a relationship?

And yet, the alternative – transplanting

modern values into the past – is worse.

It becomes laughable to see the past’s heroes and villains mouthing

politically-correct phrases, particularly when our social attitudes wouldn't

permit many features of life in the past.

Hollywood History is not real history. When it comes to setting books in the past, and

discussing touchy subjects like romance, it behooves us to remember that.

~~~

Well said, Chris. I find the current tendency to misunderstanding the mores of the time, and the trend toward revisionist history, disturbing. I am even aware of classics of literature which have been "revised" in the name of suiting some modern standard of proper behavior and speech. To me, this is an abomination – if we erase the traces of what those eras were really like, and do not teach them to our children, how can we hope to learn from our own history...which we have consequently forgotten?

And for any writer worth his/her salt, it can be a minefield to traverse the fine line between historical accuracy and not offending readers.

-Stephanie Osborn

http://www.stephanie-osborn.com