Excerpted from Kiss Your Ash Goodbye: The Yellowstone Supervolcano,

© 2018

By Stephanie Osborn

Images in this article are public domain unless otherwise

noted.

How many supervolcanoes are there in North America?

There are ~170 active volcanos in the United States of America,

most in Alaska and Hawaii, though there are quite a few along the West Coast

states.

There are only an estimated 4-5 supervolcanoes in the USA.

These include the Yellowstone Caldera (VEI:7-8), Mt. Mazama/Crater Lake

(considered dormant) (VEI:7), Valles Caldera (VEI:7), Long Valley Caldera

(VEI:7), La Garita Caldera (likely extinct) (VEI:8), with all except the last potentially

capable of erupting. There were more, but they appear to be extinct. Extinct is

relative, however; most show some degree of geothermal activity in the area.

Mt. Mazama/Crater Lake (VEI:7)

The central feature of Crater Lake National Park is Mount

Mazama in southern Oregon. It is a composite volcano (a composite of

alternating layers of ash/cinder and lava) in the Cascade Volcanic Range of the

Pacific Northwest, which are fed by the subduction and subsequent melting of

the Pacific Ocean floor tectonic plates.

Prior to the caldera-forming eruption, Mazama stood at least ~12,000ft

(3,700m) in altitude. Post-eruption, it now has a maximum height of 8,934ft (2,723m)

at Mount Scott (2mi/3km east of the caldera rim), which is a parasitic cone on

the flank of the volcano. [Yes, that’s right, the caldera rim is some 800ft+

(240m+) lower.]

The caldera rim proper ranges from 7,000-8,000ft (2,100-2,400m)

altitude, and is 5x6mi (8.0x9.7km) across. The bottom of Crater Lake goes

2,148ft (655m) down; it is the deepest lake in the U.S. The lake IS the

caldera, so that's at least how far it collapsed. Some say that the bottom is

near the base of the mountain, others that it goes even deeper.

Crater Lake, the water-filled caldera of Mt. Mazama.

In relatively continuous eruption since 420,000 years ago, things

changed around 30,000 years ago, when the chemistry of the melt feeding the

magma chamber apparently began to change from a relatively basaltic, runny

magma to a much more viscous, silica-rich melt. As this melt grew thicker, the

eruptions became more violent.

The catastrophic eruption occurred 7,700 years ago, and was

observed by the local Klamath indigenous people, who “recorded” it in myth. It

“...started from a single vent on the northeast side of the volcano as a

towering column of pumice and ash that reached some 30mi (50km) high. Winds

carried the ash across much of the Pacific Northwest and parts of southern

Canada...As the summit collapsed, circular cracks opened up around the peak.

More magma erupted through these cracks to race down the slopes as pyroclastic

flows. Deposits from these flows partially filled the valleys around Mount Mazama

with up to 300ft (100m) of pumice and ash. As more magma erupted, the collapse

progressed until the dust settled to reveal a caldera, 5mi (8km) in diameter

and 1mi (1.6km) deep.” ~USGS website

Subsequent eruptions from vents inside the caldera created what

became Wizard Island, as snow- and glacier-melt slowly filled the depression.

Eventually eruption ceased, and the ruins of Mt. Mazama began to resemble the

beautiful Crater Lake we know today.

Mt. Mazama is officially considered dormant by the U.S. Geological

Society.

The Valles Caldera (VEI:7)

Sometimes called the Jimez Caldera, this supervolcano is

located in northern New Mexico, 55mi (90km) north of Albuquerque. It is named

for the numerous grassland valleys (Spanish: valles) contained within the circular

caldera, which is about 13.7mi (22km) in diameter. It is similar to Yellowstone

in that the caldera also contains hot springs, fumaroles (steam vents), gas

vents, and volcanic domes, in addition to meadows and streams.

The Valles Caldera as viewed from the rim.

Note the

volcanic domes dotting the floor.

Credit: National Parks Service.

Geologically, it is one of the best-studied calderas in the

U.S. There are at least two known calderas on this site, the Valles, and the

older Toledo Caldera. The nearby and associated Cerros del Rio volcanic field

is older still, indicating multiple supereruptions at this site. Overall, these

and related nearby volcanic features are included within the Jemez Volcanic

Field & Mountain Range, which stretches across three counties in New

Mexico.

Several layers of silica-rich lava and tuff (welded ash) in

the region are ample proof of the eruptions, the most recent of which was some

50-60 thousand years ago and resulted in the current Valles caldera. Previous

eruptions date back at least 14 million years.

The cause of the vulcanism seems to be the intersection of

the Rio Grande Rift (a continental rift zone, running N-S from central Colorado

state, USA, to Chihuahua state, Mexico) and the Jemez Lineament (a series of

faults running E-W 600mi (965km) from Arizona east possibly as far as western

Oklahoma). The Valles Caldera does not, therefore, appear to be due to a

solitary mantle hotspot as such, but to rifting occurring in the middle of the

continental plate, though this rifting may be from convective uplift in the

mantle.

The Long Valley Caldera (VEI:7)

The Long Valley Caldera is in central California along and

slightly east of the westernmost Sierra Nevada Range. It and the adjacent

Mammoth Mountain/Mono-Inyo complex are around 55mi (89km) northeast of Fresno,

California.

Part of the Long Valley Caldera,

looking east from the

north rim.

The caldera is ~20mi (32km) long, 10mi (16km) wide, and up to

3,000ft (910m) deep. It generated a massive supereruption some 760,000 years

ago, producing the Bishop Tuff formation. The grand total of ejecta was some

150cu.mi (625km3), after which the surface sank nearly a mile (1.6km) into what

had been the magma chamber.

The cause of the supereruption is unexplained; it is not

fueled by a mantle hotspot, nor is it provided melt via subduction.

More, while it is adjacent to still-active Mammoth Mountain

and the Mono-Inyo crater chain, and at least appears to be associated with

them, the magma chemistries are very different, indicating they do not share a

common melt system, and are NOT associated. This is an interesting puzzle.

“The caldera remains thermally active, with many hot springs

and fumaroles, and has had significant deformation, seismicity, and other

unrest in recent years.” ~USGS website

The activity is sufficient to run a geothermal power plant

located there. But how much of this activity is due to the Mono/Mammoth complex

and how much to the caldera source is not fully understood. Smaller eruptions

have occurred around the caldera on a semi-regular long period, but the lava

extruded has apparently been increasingly crystalline in nature, which may

indicate that the magma source is cooling significantly.

La Garita/Creede Caldera (VEI:8)

The La Garita caldera-forming eruption is estimated as one of

the largest eruptions on Earth. It lies in the midst of a huge region in the

Rocky Mountains called the San Juan Volcanic Fields. The town of Creede sits on

what would have been the north caldera rim, with Pueblo, Colorado 110-115mi

(km) east-northeast; Colorado Springs ~120mi (193km) northeast; Denver ~150mi

(240km) north-northeast.

This region became active some 35-40 million years ago, with

an exceptional period of activity from 30-35 million years ago. At the tail end

of this flurry of vulcanism, the La Garita supereruption took place, roughly 27

million years ago. It ejected some 1,200cu.mi. (5,000km3) of

material, which became known as the Fish Canyon Tuff. This ash deposit covered

an area of AT LEAST 11,000 sq.mi. (30,000km2) in a layer whose

average depth was 328ft (100m). This tuff is surprisingly uniform chemically, indicating

it was ejected all in a volume.

The resulting caldera was a monster 22mi (35km) wide, and

anywhere from 47-62mi (75-100km) long. It is no longer recognizable as such to

the untrained eye, however, as a single resurgent dome (Snowshoe Mountain) has

filled it.

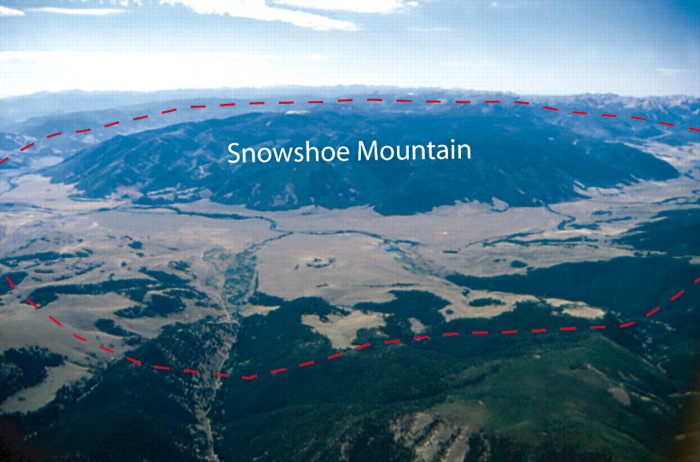

La Garita Caldera (red dotted outline),

with resurgent dome

(Snowshoe Mountain) inside it.

The energy of the eruption was some 5,000x the largest

nuclear device ever detonated on Earth, the Tsar Bomba, a 50MT explosive. This

places the La Garita supereruption at 250 GIGATONS of energy. The area

devastated would have encompassed a substantial portion of what is modern-day

Colorado, not counting ash fall.

Vulcanism in the San Juan Volcanic Field as a whole,

including the La Garita supervolcano, apparently ended 2.5 million years ago.

It is considered extinct.

What’s the strongest supervolcano ever known?

The biggest known eruption in geologic history IN THE USA —

some say in the world — was the Fish Canyon eruption in the La Garita

megacaldera.

The biggest known eruption in geologic history in the WORLD

was the Guarapuava-Tamarana-Sarusas eruption in South America. The eruption

occurred ~132 million years ago, produced an estimated 2,100 cu. mi. (8,600 km3)

of ejecta, and was probably at least the equivalent of the La Garita eruption.

To obtain a copy of Kiss

Your Ash Goodbye: The Yellowstone Supervolcano by Stephanie

Osborn, go to: http://bit.ly/Kin-KYAGTYSV.