http://www.stephanie-osborn.com

I'm pleased to welcome back Barb Caffrey, book reviewer, editor extraordinaire, and newly-published author of the delightful fantasy/romance/comedy/mystery genre-crosser, An Elfy On The Loose. Today she talks about character development, and she does so from a broad range of experience in literature.

I'm pleased to welcome back Barb Caffrey, book reviewer, editor extraordinaire, and newly-published author of the delightful fantasy/romance/comedy/mystery genre-crosser, An Elfy On The Loose. Today she talks about character development, and she does so from a broad range of experience in literature.~~~

Barb:

Without characters, you don't have

a story.

I mean, think about it: Who'd

remember the Harry Potter series if Harry Potter wasn't there? Or his buddy Ron

Weasley? Or his other buddy, Hermione Granger? And that's just the good

characters.

What about the enigmatic Severus

Snape, the villainous Voldemort, or Harry's own uncle and aunt? Without them

factoring into the equation, how would the seven books about Harry Potter

interest anyone?

What about the enigmatic Severus

Snape, the villainous Voldemort, or Harry's own uncle and aunt? Without them

factoring into the equation, how would the seven books about Harry Potter

interest anyone?

No, books are built on characters.

It can't be any other way.

Even in a story where it's all

about one man's struggle against the elements – such as Ernest Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea or the movie 127 Hours, the true story of hiker Aron

Ralston (who had to amputate his own arm in order to survive) – you still must

buy into the main character's dilemma. You have to care about Hemingway's old

man. You have to care about Aron Ralston (as played by actor James Franco). Or

the story doesn't make any sense.

Even in a story where it's all

about one man's struggle against the elements – such as Ernest Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea or the movie 127 Hours, the true story of hiker Aron

Ralston (who had to amputate his own arm in order to survive) – you still must

buy into the main character's dilemma. You have to care about Hemingway's old

man. You have to care about Aron Ralston (as played by actor James Franco). Or

the story doesn't make any sense.

And it's always been this way.

Consider, please, that Geoffrey

Chaucer's Canterbury Tales were all

about characters. The ones we remember best, such as the stories about the

gregarious and lascivious Wife of Bath, are because the characterization was so

strong, people just couldn't help getting sucked into the tale.

Consider, please, that Geoffrey

Chaucer's Canterbury Tales were all

about characters. The ones we remember best, such as the stories about the

gregarious and lascivious Wife of Bath, are because the characterization was so

strong, people just couldn't help getting sucked into the tale.

The biggest and most obvious

example, though, is the Bible. There are so many memorable stories there –

stories of Moses, of David and Goliath, of Samson and Delilah, of wise King

Solomon, and of course last but certainly far from least, Jesus of Nazareth.

Most of these stories have narratives we completely understand.

For example, Moses tells the

Egyptian Pharoah that if the Pharoah doesn't let Moses's people go, Egypt will be

afflicted. The Pharoah doesn't listen, Egypt gets ravaged, and finally

after a great deal of suffering, the Pharoah tells Moses to take his people and

go.

Mind, if this particular story wasn't in the Bible, we'd see it as a

story of action, adventure, mayhem, perhaps even as fantastic...but it

works predominantly because we believe Moses is a grounded, down-to-Earth

person who's telling the flat truth at all times. We also believe the Pharoah

doesn't understand who – or Who – he's messing with, so when the Pharoah (and

by extension, all of Egypt )

gets his comeuppance, the reader can clap and cheer. (Or at least want to do

so, which is one reason why the Bible is among the best-selling books of all

time.)

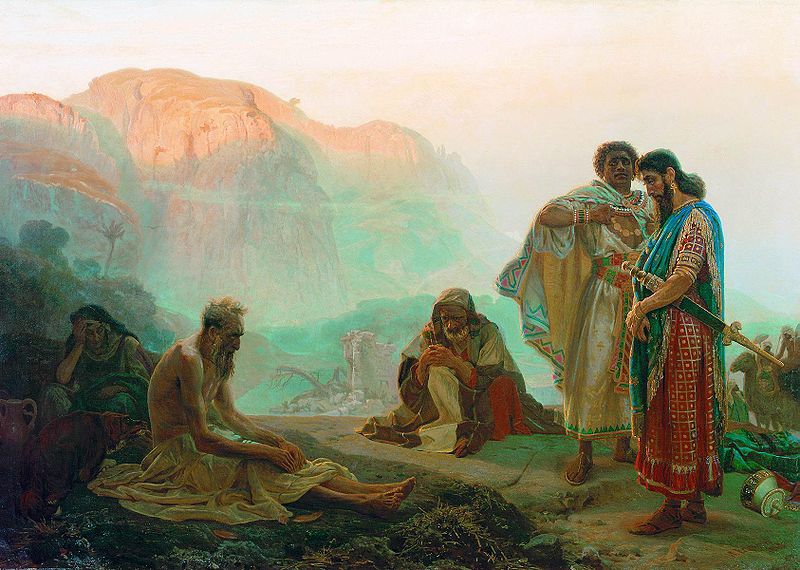

But there's a different Biblical

story I'd like to discuss, and that's the story of Job. He's a guy who

seemingly has it all at the beginning of his story, and is described as being

both "blameless" and "upright." He has a good family, lots

of money, lots of property, is well-respected, and has many friends. But because

his life is so comparatively easy, Satan turns to God and says, in essence,

"Hey, Job has it really easy. I bet he'd not be so good if he had nothing

at all."

God's reply is to cause Job to be

afflicted with a great deal of unnecessary suffering. Job has no idea why he loses

everything, why his family suffers right along with him and most of them die –

all he knows is that God has apparently forsaken him, when Job himself hasn't

done anything at all to deserve this. And all but a few friends desert him, too

– and the few friends left all believe Job must've done something to cause this, even if they don't know what.

Job, though, really is as good as

God said he is. So Job keeps being himself, tries to help others, and while

he's obviously and understandably upset at all the undeserved misery that's

befallen him and his family, he doesn't lash out at other people.

Because of Job's exemplary

behavior, eventually much is restored to Job, though Job never gets a true

answer as to why this happened. Instead, God basically stays above the fray and

says Job cannot judge God – and Job accepts this.

Now, why does much of this story

work, even to modern readers who don't accept that a Deity figure would ever

behave in such a peremptory way? Well, it's simple: We all know people who've

suffered unnecessarily cruel things. We don't know why this has happened.

Often, the ones suffering get hectored by their friends, the same as Job was,

and that just adds insult to injury. And finally, we respect a man who has

shown he truly is good, deep down, in all the ways that count – because anyone

can be a good person when there's no adversity in his life.

But it takes a very strong person

indeed to be good when everything's stacked against him.

In Job's story, we have two main

characters – God, who we can't possibly understand, and who even says so. And

Job, who we definitely do understand

. . . so if we didn't buy into Job's character, why would the story of Job

still be resonating millennia after it was originally written down?

Job's story in particular

illustrates why characterization is so important. Because if you don't have

someone memorable to build a story around (like Job, Moses, Harry Potter, the

Wife of Bath, or my own Bruno the Elfy), what good is the story? Who will

remember it? And why should anyone care?

So when you sit down to write, make

sure your main character – whether he's human, Elfy, completely alien, Godlike,

or many other disparate things – is memorable. Because without that, you can't

possibly interest a reader.

~~~

Well, it seems appropriate at this point to simply say, "Amen"...

If you haven't read Barb's new book, An Elfy On The Loose, by all means, do so!

-Stephanie Osborn

http://www.stephanie-osborn.com